December 2000 |

|

It was a time, all right ...

We need to break out the record. This is back in 1962 or so. It was pay for play. That's what promotion was all about. A hundred, a few hundred bucks. Five hundred, a thousand copies of the record that they could take down to the store to sell.

So this D.J. -- he's like a midget, this guy, about four and a half feet high--I guess he figures he's a big shot. He takes the money, but he don't play the record. What he does, he goes on the air, says, 'I'm about to break this new record." And then he breaks it--I mean, breaks it, cracks it into pieces-says, 'I wouldn't play this record if my mother gave it to me." Like I say, I guess this little prick thinks he's something. Maybe all that candy-ass Chicago tough-guy shit went to his head. Anyway, he wasn't in Chicago no more. This was New York.

It was said that Hymie Weiss, the Romanian-born Jew who had founded Old Town Records in the cloakroom of the Triboro Theatre in Harlem in 1954, chose to call his label by that name because his brother and partner, Sam Weiss, had been working for a Brooklyn paper company called Old Town and had a lot of stationery bearing that name. Hymie remembers his first act as "a guy named Cherokee," remembers that he sold the guy "a car that wouldn't start unless you pushed it downhill."

Old Town survived through black doo-wop groups, such as the Solitaires, who achieved local success in the northeastern golden triangle of New York-Newark-Philadelphia. The label would later prosper with national hit records by Arthur Prysock -- Hy's favorite-and the Earls, a white doo-wop group from the Bronx. Within a year of Old Town's inception, Hy moved into a real office, down on Seventh Avenue, and by 1958 he was operating out of 1697 Broadway, just up the road from the cathe-dral of the music business, the Brill Build-ing, 1619 Broadway, at 49th Street.

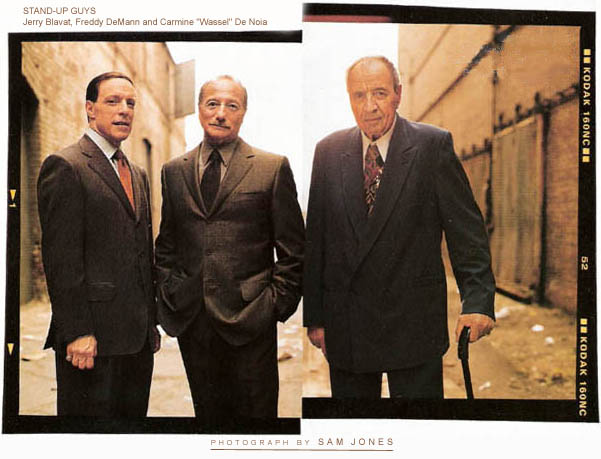

After the Chicago disc jockey's act of insolence, Hy Weiss arranged a meeting with him at the Old Town office, which was on the ninth floor. The record wasn't Hy's; he was only acting as an intermediary for the aggrieved parties. Also present was Carmine De Noia, a Broadway bookmaker who was a friend of those in the music business. Carmine was an imposing man. His friends called him Wassel, a nickname derived from his boyhood mis-pronunciation of the word "rascal."

"I used to help them," Wassel says, not much less imposing today, at 75, than he was in the old days. "See, I was the only Italian guy on Broadway, and I didn't take no crap from nobody. I respected everybody, but nobody would fool with me because I would never rob anybody."

Wassel laughs, his memory wandering back over 40 years, his voice deep, sonorous, and disarmingly blithe. "Hy goes into the other room. So here's this disc jockey. And I'm looking at him, and he's, like, this little midget. I throw open the window, pick him up, flip him, shake him out by the ankles. Ninth floor. All the change fell out of his pockets. Some friends of mine picked it up."

The disc jockey played the record during his very next broadcast, and he kept playing it. Soon, however, he was back in Chicago.

"He denied it ever happened," Wassel says. "Some guys asked him. He denied it. I said, 'Let him deny it. That's all right. Let him deny it.'"

"See," says another old-timer, "it wasn't that this guy didn't want to play the record. It was that he took the money, then didn't play the record. He wasn't a stand-up guy."

"Same thing as today, lot of fakers." We are sitting around a big table in the back room of a restaurant-much talk of recent surgeries and current medical condi-tions; much ordering of eggs and sausages to be prepared in exacting and arcane Ital-ianate manners; and then the stories.

"Yeah," says Wassel. "I remember, there was this song I liked-and Sid Weiss"-a songwriter, no relation to Hy-"gave the publishing on it to me. So what am I gonna do with it now? Am I gonna put it on the wall? I don't know anything about publishing."

Wassel got a telephone call from a song publisher whose name is lost to the years, as is the name of the song in question.

"Yeah."

"You got a song we want."

"I don't want no trouble."

"We want the song."

Wassel wrapped a length of pipe in a rolled-up newspaper. "I went up there, and the guy was a nasty guy. If he would've talked nice to me, I would've gave it to him. I didn't care; I didn't know anything about publishing. So, anyway, I went up there. This guy's sitting at his desk with his feet on the desk."

"Listen," Wassel told the guy, "what do you want?"

"You know what I want. Just put the song over there."

Wassel looked at him. "I says, 'Here.' I came down with the pipe. I broke everything. The desk, everything."

Had the would-be wiseguy asked, he would have received. But, as Wassel says, "he was trying to shake me down."

Everybody was trying to shake down everybody.

Jubilee Records, founded in Washington, D.C., in 1946 by Herb Abramson, and taken over by Jerry Blaine in 1947, epitomized the scattershot approach of the mongrel labels: record, buy, or lease anything you could, get it out there, and see what shook.

It was in June of 1952 that young Freddy Demann of Brooklyn began working for Blaine as a promotion man … DeMann, who 21 years later became Madonna’s manager, remembers Blaine as a gruff-speaking man given to lavish excess… Blaine, however, gave DeMann nothing in the way of pay-for-play gelt when he sent him out in 1962 to promote “I Love You,” by the Volumes, on the new Chex label. Without the cash, DeMann discovered, the record was trash.

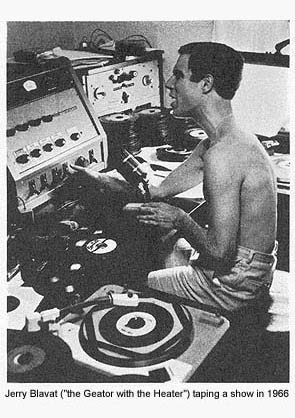

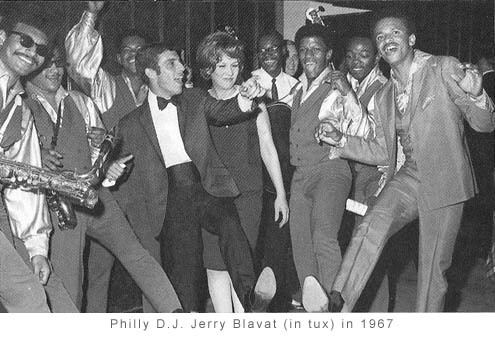

In the end, without any cash to slip into the sleeves of “I Love You,” Freddy, after a long, roundabout journey among unresponsive disc jockeys, found himself in Philadelphia. It was there, in the studio-office of D.J. Jerry Blavat, that he laid down his lantern. “So, anyway,” Blavat tells me, “I’m doing the radio show, and the promotion men come to see me. I get a knock at the door, and I say to Kilocycle Pete" -- a kid who worked at the station – “ ‘Answer the door,' which he normally does. "So it's this young guy. His name is Freddy DeMann. He says, 'I got a record I want you to listen to, and I've got a problem.' I said, 'What's the problem?' He says, 'Nobody will play this record. You're my last resort. I'm gonna lose my gig.' He says, 'There's no money on this record. I have no money for the record.' I said, 'Freddy, let me tell you something. Number one, I don't take money. If I like the record, I play it. My mother can come to me with a record and say, "Your uncle made this record." If I don't like the record, I'm not gonna play it. Because for my teenagers, for my audience, I have in my mind the sound I'm gonna present.' To make a long story short, he sits with me while I do the radio show. I listen to the record. I flip over the record. Nobody wants to play the record because they're all looking for this" -- he rubs his thumb and two fingers in the universal baksheesh gesture --"and he doesn't have it. I play the record, bust the record wide open. From that moment on, Freddy DeMann and I became friends. His boss, Jerry Blaine, wanted to know, 'How did you get the Geator to play this record with no money?’” (That's Blavat, see, the Geator with the Heator, etymology approximately as follows: the nickname Geator derived from the nickname Gator so as to now rhyme with heater, as in let's-get-down-with-the-sound-and-turn-that-car-heater-up-on-this-cold-Philly-night.) "And Freddy explained to him, 'He liked the record, man, he liked the record.' And that's the way I was from the very beginning to now. You could be my best buddy, but if I don't like the record, I'm not gonna play it." Blavat was 22 years old and making over a hundred grand a year. "I mean, back in 1962, that's a lot of money for a little cockroach kid from South Philadelphia."

C'era una volta a Filadelfia ... Gerald Joseph Blavat was born, in Philly, on July 3, 1940. "See," he says, "when I was a kid growing up, there were four corners in the neighborhood. Pat's Luncheonette, the grocery store, the Tap Room, and a variety store. These were the four corners of South 17th and Mifflin Streets. The younger guys hung on one corner. Across the street were the older guys. Then, in the Tap Room, were the older wiseguys. And the variety-store corner, the people in the neighborhood would come in and buy blah, blah, blah, I don't know. And up the side street, the older guys would shoot craps. "When you grew up in that neighborhood, you knew everybody. You knew everybody. They used to call me Shorts when I was a kid because I was the smallest little guy. But I always knew and respected older people. When I was 12, I was hanging out in the social club with guys 17, 18 years old. By the time I was 16, I was donning a black Stetson, black Continental suit, going into clubs and bars. But I knew how to act, so I always acted older."

Like the Mob in America, Jerry was Jewish and Italian. His father, known as Gimpy Lou, or simply the Gimp, was with the Jewish crew. "He was in the numbers business. When I was a kid, they would ship me off to a day nursery at St. Monica's at six in the morning. We lived in a row house on a street where there were only six houses -- everything else was garages -- and our house would turn into a bookie joint with all the top Jewish guys working it. Moishe, Sammy, Mickey. When I came home from the day nursery at five, it would turn back into a regular house."

"These kids were innocent," Jerry says. "I used to get them laid. That was the biggest thing they wanted to do. I was a kid, 18, on the road. I would take them to, say, Wheeling, West Virginia. One time I went in, and I think it was 10 bucks apiece to get laid. They were only making 40 bucks a week. I handled all the money. So the one kid wanted to get fucked a second time. I said, 'You just got laid -- you're not gonna be able to get it up.' Yeah, yeah, yeah. 'I'm in love with this fuckin' broad.' So I made a deal with the madam: 'He wants to go a second time.' She said, 'O.K., give me eight dollars.' He went back up to the room, and we're all waiting. The madam came and said, 'Look, he's gotta be outta there very shortly.' We're still waiting. The madam comes and she says, 'I'm getting him out of here.' She goes upstairs. I hear a commotion, yelling and screaming. He doesn't wanna leave until he gets a hard-on. She comes back down, she calls the cops. The cops come, and they almost pinch us because it was protected. He wants his money back, the eight bucks. I said, 'Fuck you and your fucking money -- let's get out of here.'"

As immensely successful as it was, "At the Hop" was pretty much the end as well as the beginning of Danny and the Juniors. When Blavat came off the road with them for the last time, in 1960, they were fading fast; Danny Rapp would go on to commit suicide in the spring of 1983, aged 41. In 1960, however, Jerry was just getting started.

"There was this night-club in South Philadelphia called the Venus. And, remember, this is when rock 'n' roll is not being featured in clubs. I mean, this was a lounge where wiseguys would go and drink and pick up broads and things like that. I mean, it was the Venus Lounge in South Philadelphia. So I had just made a score coming off the road. I think I had, like, 800 bucks, and I started to shoot craps at 17th and Mifflin with the older guys. And Don Pinto, who owned the club. was there. Guys were making bets. One guy says to Pinto, 'Yeah, he can help ya. What do you need?' He said, 'I'm gonna do a radio show out of my club.' This guy said, 'The kid can do it.' I said, 'Yeah. I'll do a radio show.' So came to be the Geator with the Heater, keeper of the flame and coolest of the cool. Thirty-eight years is a long time, and Blavat and DeMann have seen a lot of things come and go, a lot of things go and come through those years, including themselves, a few times over. Sitting with Jerry in New York, Freddy after a while seems to slough the skin of Los Angeles, where he has for so long lived and worked as a manager and label executive. It is as if a breeze from Brooklyn, a breeze of the past, reclaims him. They reminisce about the days and characters gone. They were days of naivete and exuberance: the sweet and celibate two-straws-and-a-milk-shake songs of Paul & Paula, the Singing Nun rising to the top of the pop charts. And, beneath it all, as Juggy Gayles had put it: booze, bribes, and broads. Well, the Singing Nun is gone. She OD'd on pills in a suicide pact with another woman in the spring of 1985. But it's not the Singing Nun that these guys miss. "Yeah, Abner was the best," muses Jerry. "In New York, when I first broke in, there was a little ring of whores that everyone knew," says Freddy. That was the way it was. Some took their bribery in the currency of flesh, and for others it was both money and broads. "I was always on the look-out, you know, who's gonna hook me up. When I went to Chicago, I got the names of three people to call for whores, and that was mandatory. Well, actually, he gave me one name and he gave me the name of Abner. I went to see Abner, just to say, 'Hi, I'm new in town.' And he said, 'O.K., here, you need some whores?' I said, 'Yeah.' 'Here's three, call them and use my name. And meet me every Friday night at the Avenue Motel. We have a bunch of guys coming around, and we all hang out, have drinks, and you look like a cool guy -- you can come' I was white and they were black. I would go every Friday to that Avenue Motel, and, man, I'm telling you ... “ Freddy shakes his head: there are no words. “Abner drank Johnnie Walker Black straight up, and so I drank Johnnie Walker Black straight up. With a soda chaser."

They're talking about Ewart G. Abner Jr., who ran Vee-Jay Records, a company that had been founded in Gary. Indiana, in 1953,by Vivian Carter and her husband. James Bracken -- Vee for V. Carter. Jay for J. Bracken -- and had moved to Chicago in 1954. From the beginning -- Vee-Jay's first release, by the Spaniels, a quintet formed at Roosevelt High School in Gary, established the group as one of the leading doo-wop acts of the Midwest -- the company was one of the most powerful of the independents, strong in the full spectrum of R&B from the Spaniels to the Dells, and from Jimmy Reed to John Lee Hooker. In 1963, under Ewart Abner –- who, with the benison of Carter and Bracken, was the guiding force of the label -- Vee-Jay became the Beatles' first American label. It was Blavat, the year before, who had convinced Abner that Vee-Jay could prosper with white artists as well as black, bringing him a quartet of Italian-American kids from New Jersey, the Four Seasons, who had a song called "Sherry," which became a No. 1 pop hit and a No. 1 R&B hit for Vee-Jay in 1962. Abner was so cool that he wore velour jumpsuits when everyone else was wearing suits and ties. He died two days after Christmas of 1997, aged 74. How I would love to have included the words of that voice, so recently but forever lost. I mean, damn, velour jumpsuits.

It was some convention. Freddy: "I remember that pussy-eating contest. What was his name? He was fairly short, chubby. It was Atlantic Records that he worked for. He and this other guy, this local promotion man out of Philadelphia." Jerry: "The guy from Atlantic used to don a robe and come out like a fighter. I don't remember if it was how many they could do, or how long they could do it, or what." "It was how long it would take for them to get the broads off." "It was a spectacle. People were laying bets." But with promotion men involved, suspicions of pay-for-play pseudo-orgasms were not to be dismissed out of hand. "But I'm telling you," Jerry says. "It had to be for real." He adds: 'Im gonna tell you exactly when this convention was. My wife was pregnant with my second child. Stacey was born June the 27th. This convention was, like, June the 20th, because I didn't wanna go home, because I knew Patty was due any day, and I didn't wanna really ... " "Yeah, it's where everyone made the deals to get records played."

It was a time, all right. But as Heraclitus, greatest of pre-Socratic promotion men, long ago said: Nothing abides. By 1980, when the gladiatorial cunnilinguists had many years since hung up their robes, the Geator with the Heater looked like he was down for the count …. They All Sang On the Corner. So the title of a book about doo-wop, written more than a quarter of a century ago, by Philip Groia. It is a title that captures and expresses much. For, from the beginning, rock 'n' roll was of the corner: those four corners of Blavat's youth, and the countless corners of countless youths. Rock 'n' roll, in all its innocence, in all its wickedness, was, from the beginning, of the neighborhood. And as the Church comprises many churches, so the neighborhood -- I cannot capitalize that initial n no matter how strongly effect and meaning entice me to do so, for, here, to exalt the word would be to misrepresent the thing -- comprises neighborhoods beyond number. This is not an idle analogy: the neighborhood is, or was, the embodiment of a spiritual ethos as supernal and puissant in reality as that of the Church in theory. As every neighborhood was a parish, and every parish was a neighborhood, so together they have died.

These may sound to some like words beyond good and evil, but not to one who was neighborhood-born, Blavat was from the neighborhood. He was from the old school. But the walls of the old school came tumbling down.

Jerry had been doing good …. He had been spreading the old-time religion to converts, laying down that lean, mean music to those who had been following him for years. He was on radio. He was on television. He promoted shows. He had music stores, the Record Museums. He owned a club, Memories, in Margate, New Jersey. He was a partner in the best of the early oldies labels, Lost Nite, reissuing, with the help of Ewart Abner and Morris Leyy, some of the finest recordings of the 50s. Most of his income came from hosting shows – no, "hosting" is not the right word. The Geator performed. I have heard of mercury poisoning. To experience the Geator in action was, and is, to witness what might be called adrenaline poisoning. If you talk to every survivor of the days of pay-for-play innocence and of experience, among all the names bandied about, in malice or in joy or in both, Blavat's is one of the few that remain unsullied. He never took, they say. He was his own man, who had the wits and the ways to make it his way. Even when he got Crewe and Abner together, bringing about one of the biggest hits in the history of Vee-Jay, he refused the points that were offered him for "Sherry": a perfectly legitimate and legal offer that he chose simply not to accept.

He loved Crewe he says. He loved Abner. He loved the record. He was making a fortune as it was. He never wanted to be beholden or have his freedom endangered, and that was that.

Jerry's not down anymore. He brought himself back up, starting over as he had started out after that crap game way back when: buying time, selling blocks on WCAM. Today he's broadcasting, over five different radio stations heard in southern Jersey, Philadelphia, and Delaware, and doing shows on WQED, a Pittsburgh PBS channel. He's still got his club in Margate. That adrenaline is rushing as wild as ever. He hosts live shows and what he still calls "record hops," taking down up to $1,600 for a weeknight gig, $2,500 to $3,500 for a weekend night. And if I had half of Freddy DeMann's money, I tell him, I'd burn mine. Yet even Freddy, sitting there shed of his L.A. skin, gives the impression that there were joys back there, in those days before truly big money, that have not returned. "Phil Kronfeld's men's shop," he recalls wistfully. It was where la creme de la cool bought their threads. "I was making $50 a week or something like that, looking through that store window. I dreamed that someday I could afford to go in there and get a suit like the rest of those guys. That sharkskin suit and that silk tie, man. I had to have it. I had to do it." Blavat has his own wistfulness. I don't even know if he and DeMann are hearing each other's words, or hearing merely the wistfulness.

"Hell," says DeMann, "later on, when I was a manager, you know how many guys approached me? I remember there was a guy came in with a suitcase full of cash when I represented the Jackson 5. He wanted to be the promoter of a tour the Jacksons were going to do. I said, 'Ah, come on, you're broke. I hear you're broke.' 'Here, here, here'-- he's pulling bundles out of the case." "Was he a successful promoter?" I ask. "He was. He did a lot of national tours, and then went to jail for tax evasion or something, I don't know." No, the two of them agree, payola never died. It just became a drag. "Payola today," says DeMann, "goes on in a much bigger way. Now the stations absolutely hold you up. KISS in Boston, KISS in L.A., they're doing a big summer show, or their Christmas show, and it's 'Here's the act we want.' And you better supply them or they won't play your record. They don't say it, but that's what they mean." Freddy shakes his head, waves aside the current music business and its million-dollar corporate shakedowns, while Jerry turns back to the days when the racket was exciting. "Who pulled the line, who wasn't gonna pull the line. Who got paid. I'm telling ya, it was incredible. The record business was like a Damon Runyon thing, but with people who knew nothing about the record business." And all the while, the kids dancing, aswirl, their own pulses singing, never knowing, never hearing, the beat beneath the beat. "Music was different," says DeMann. "The Mafia was different. There was honor among thieves. Now there isn't any. There's nothing. There's nothing to hang your hat on these days."

|

|

Another day. I'm in New York with Wassel, Hy Weiss, and other characters. Freddy is gone back to L.A., but these guys are saying what he said in their own ways.

"Dead, all of it," somebody says.

"They took away the prize."

"Yeah," as Wassel says, intoning agreement with nothing, but merely dismissal. "No more stand-up guys anymore." It is a once common complaint, heard ever more rarely, testimony perhaps of its increasing truth. "This city's dead," says someone else. "This guy, this mayor, this faccia di morte here, he's ... " The speaker shakes his head, not for want of words, but in disgusted velleity.

Wassel hasn't been to jail in a while. I tell him of an arrest less than a year ago: the first time I was ever in a cell without a single obscenity scrawled on the walls. The walls were filled with only two phrases, in a hundred hands, a hundred intensities: KILL RUDY and DIE RUDY DIE. The notion seems to please all at the table, and inspires Wassel to speak again.

"Yeah" -- same tone. "People say this guy's like Mussolini. They say he's like Hitler. I tell 'em no. Mussolini and Hitler had friends."

Even Hy Weiss grins. Then he leans forward, softly says, "You know why the government will never get the music business? It's because they could never understand how it works. And you know why that is? It's because the people in the music business have never understood how it works"

Then Hy Weiss, a boyish gleam in his 77-year-old eyes, returns quite calmly to his eggs and his coffee and his silence.

Rock on, Hymie, rock on.

|

So, anyway, this character, this punk of a disc jockey from Chicago, ends up working here in New York. We had this record, nice little record, "Just One More Tear," by a girl named Laurie Ann Mathews. She was good. She was white, but she sounded black.

So, anyway, this character, this punk of a disc jockey from Chicago, ends up working here in New York. We had this record, nice little record, "Just One More Tear," by a girl named Laurie Ann Mathews. She was good. She was white, but she sounded black.

"Your name Wassel?"

"Your name Wassel?"

Blavat had been one of the kids who danced on the WFIL-TV show American Bandstand in the days before the show's original host, Bob Horn -- banished in the wake of scandals involving drunk driving and allegations of sex with a minor -- was replaced, in the summer of 1956, by Dick Clark, the cultural hygienist whose smile of cleanliness and rectitude was the smile of milk-and-cookies rock 'n' roll. Another of the dancers from the Horn show, Danny Rapp, had helped to form and was the lead singer in a local group called the Juvenairs. In 1957 the group became Danny and the Juniors. Their first record, "At the Hop," released toward the end of that year, was one of the biggest hits of 1958. When the group set out to tour, it was with Jerry Blavat as their road manager and shepherd.

Blavat had been one of the kids who danced on the WFIL-TV show American Bandstand in the days before the show's original host, Bob Horn -- banished in the wake of scandals involving drunk driving and allegations of sex with a minor -- was replaced, in the summer of 1956, by Dick Clark, the cultural hygienist whose smile of cleanliness and rectitude was the smile of milk-and-cookies rock 'n' roll. Another of the dancers from the Horn show, Danny Rapp, had helped to form and was the lead singer in a local group called the Juvenairs. In 1957 the group became Danny and the Juniors. Their first record, "At the Hop," released toward the end of that year, was one of the biggest hits of 1958. When the group set out to tour, it was with Jerry Blavat as their road manager and shepherd.

So Don said. 'I'll bet you on the next fuckin' throw you can't do it.' I said. 'Don't bet your money on the fuckin' throw, 'cause you're gonna lose. I can do a radio show from your club.' He rolls, he lost. He didn't get the fuckin' number. So he says. 'Bad day.' I say, 'I'm gonna make it up to you. You're gonna see, I'm gonna do a radio show.' I went up to WCAM in Camden. I said to the general manager there, 'I wanna buy an hour's worth of time. What would it cost me?' He said, 'A hundred dollars.' I said, 'O.K. How long?' He said, 'Thirteen-week contract.' I got him $1,300, and I had the contract. I went back to Don Pinto and his partners at the Venus. I said, 'Look, I'll do an hour's radio show. I want you to give me 120 bucks.' I then went out and I sold 15-minute blocks. Freihofer bread, 60 bucks. Crisconi Oldsmobile, 60 bucks. Dale Dance Studios, 60 bucks. Seven Up, 60 bucks. I made $240, and I had $120 from the club. Whoever comes through- ~ Tallulah Bankhead, Rocky Graziano -- I interview them at the club. Then one day a snowstorm hits the city, closes down the club. I owned the radio time. So I took my records up to Camden and started to play that music. The snow kept coming down, the kids were off from school" -- he snaps his fingers: dual double-finger snaps, the loudest snapping known to man -- "and that was that."

So Don said. 'I'll bet you on the next fuckin' throw you can't do it.' I said. 'Don't bet your money on the fuckin' throw, 'cause you're gonna lose. I can do a radio show from your club.' He rolls, he lost. He didn't get the fuckin' number. So he says. 'Bad day.' I say, 'I'm gonna make it up to you. You're gonna see, I'm gonna do a radio show.' I went up to WCAM in Camden. I said to the general manager there, 'I wanna buy an hour's worth of time. What would it cost me?' He said, 'A hundred dollars.' I said, 'O.K. How long?' He said, 'Thirteen-week contract.' I got him $1,300, and I had the contract. I went back to Don Pinto and his partners at the Venus. I said, 'Look, I'll do an hour's radio show. I want you to give me 120 bucks.' I then went out and I sold 15-minute blocks. Freihofer bread, 60 bucks. Crisconi Oldsmobile, 60 bucks. Dale Dance Studios, 60 bucks. Seven Up, 60 bucks. I made $240, and I had $120 from the club. Whoever comes through- ~ Tallulah Bankhead, Rocky Graziano -- I interview them at the club. Then one day a snowstorm hits the city, closes down the club. I owned the radio time. So I took my records up to Camden and started to play that music. The snow kept coming down, the kids were off from school" -- he snaps his fingers: dual double-finger snaps, the loudest snapping known to man -- "and that was that."

"I got him to pick up 'Sherry' at the 1962 convention, down in Miami, at the Fontainebleau. Association of Record Merchandisers," says Blavat. "I was with Morris Levy. I bump into Bob Crewe, who I knew forever. He wrote 'Silhouettes.' He says, 'I want you to hear something I just cut with these kids. It's a song called "Sherry.'" I hear it. I said, 'I think this fuckin' thing's a hit.' I play it for Morris; he says, 'That's the worst piece of shit I've ever heard.' I say. 'Crewe, don't get discouraged.' Now, Abner loves me for my ear, O.K.? Between 'He Will Break Your Heart,' by Jerry Butler, which I busted wide open for him, between this,that, the other thing -- I mean, God gave me an ear. I take Crewe up to Abner's suite. Abner hears it. He says. 'You know, Geator. I think you got something here. But it's a white artist.' I said. ‘Abner, who the fuck knows the difference on an acetate or a record if it's white or black? If a hit's a hit, it's got no fuckin' color, man.' They make a deal. I've got this kid with me who works for me in Philly. He's an orphan, maybe 15 or 16 years old. Crewe wants to celebrate. I say, 'This kid's never been laid -- let's get him a hooker.' I go downstairs. Three hours later, I go back to the room. There's broads and characters all over the place, and there's this kid swapping spit with this fuckin' hooker that's been blowing everybody. He's naked, he's got a sheet around him: it's like a Roman orgy. He says, 'I'm in love.' I said, 'Forget about it.' The kid said, 'Why? She loves me.' I said, 'She's a hooker.' The kid turns white: 'No.' I have a drink in my hand. He spins around, goes to hug me from behind, I go down on the bed, the glass shatters, there's blood all over, the kid faints, they rush me to St. Joseph's. Forty-two stitches."

"I got him to pick up 'Sherry' at the 1962 convention, down in Miami, at the Fontainebleau. Association of Record Merchandisers," says Blavat. "I was with Morris Levy. I bump into Bob Crewe, who I knew forever. He wrote 'Silhouettes.' He says, 'I want you to hear something I just cut with these kids. It's a song called "Sherry.'" I hear it. I said, 'I think this fuckin' thing's a hit.' I play it for Morris; he says, 'That's the worst piece of shit I've ever heard.' I say. 'Crewe, don't get discouraged.' Now, Abner loves me for my ear, O.K.? Between 'He Will Break Your Heart,' by Jerry Butler, which I busted wide open for him, between this,that, the other thing -- I mean, God gave me an ear. I take Crewe up to Abner's suite. Abner hears it. He says. 'You know, Geator. I think you got something here. But it's a white artist.' I said. ‘Abner, who the fuck knows the difference on an acetate or a record if it's white or black? If a hit's a hit, it's got no fuckin' color, man.' They make a deal. I've got this kid with me who works for me in Philly. He's an orphan, maybe 15 or 16 years old. Crewe wants to celebrate. I say, 'This kid's never been laid -- let's get him a hooker.' I go downstairs. Three hours later, I go back to the room. There's broads and characters all over the place, and there's this kid swapping spit with this fuckin' hooker that's been blowing everybody. He's naked, he's got a sheet around him: it's like a Roman orgy. He says, 'I'm in love.' I said, 'Forget about it.' The kid said, 'Why? She loves me.' I said, 'She's a hooker.' The kid turns white: 'No.' I have a drink in my hand. He spins around, goes to hug me from behind, I go down on the bed, the glass shatters, there's blood all over, the kid faints, they rush me to St. Joseph's. Forty-two stitches."

The true gauge of the freedom of any community is the measurement of the degree of equality with which the fruits of malfeasance are shared by the rulers and the ruled, the cop on the beat and the man or woman on the street. The essence of democracy, as of capitalism, is corruption. Only when the criminal in blue and the criminal in mufti, the peddler and the priest, and the alderman and the drunkard -- only when they are neighbors of common root and conspiracy is any neighborhood safe for the old lady on the stoop on a hot summer night; only then is there true charity, only then is there a justice that is real, and only then is there life in the air. As the social clubs close, so the churches empty. This is fact, not metaphor.

The true gauge of the freedom of any community is the measurement of the degree of equality with which the fruits of malfeasance are shared by the rulers and the ruled, the cop on the beat and the man or woman on the street. The essence of democracy, as of capitalism, is corruption. Only when the criminal in blue and the criminal in mufti, the peddler and the priest, and the alderman and the drunkard -- only when they are neighbors of common root and conspiracy is any neighborhood safe for the old lady on the stoop on a hot summer night; only then is there true charity, only then is there a justice that is real, and only then is there life in the air. As the social clubs close, so the churches empty. This is fact, not metaphor.

“I'm having coffee one morning at my place with Blinky" -- Jerry's talking about Blinky Palermo, the Philadelphia-based prince of the fight rackets under the lordship of Frankie Carbo -- "and the phone rings. It's Sinatra. He calls me Matchstick; that's what he always called me. 'Where's the raviolis?' Blah, blah, blah. I said, 'My mother's making the raviolis. They'll be there by six, all right?' So Blinky's with me. He says, 'Who was that?' I said it was Sinatra. He says, 'That bum. I haven't seen him in --' I said. 'Well, I'm going over with the raviolis and the meatballs and the sausage. Come back at 5:30. We'll get the limo and we'll go and you'll say hello to Sinatra.' Sure enough, he comes back. We get in the limo with the raviolis, the meatballs, the sausage, and we go see Frankie." For a moment, it's not the past: "Frank loves my mother's raviolis. Because she's abruzzese. They're the best cooks."

“I'm having coffee one morning at my place with Blinky" -- Jerry's talking about Blinky Palermo, the Philadelphia-based prince of the fight rackets under the lordship of Frankie Carbo -- "and the phone rings. It's Sinatra. He calls me Matchstick; that's what he always called me. 'Where's the raviolis?' Blah, blah, blah. I said, 'My mother's making the raviolis. They'll be there by six, all right?' So Blinky's with me. He says, 'Who was that?' I said it was Sinatra. He says, 'That bum. I haven't seen him in --' I said. 'Well, I'm going over with the raviolis and the meatballs and the sausage. Come back at 5:30. We'll get the limo and we'll go and you'll say hello to Sinatra.' Sure enough, he comes back. We get in the limo with the raviolis, the meatballs, the sausage, and we go see Frankie." For a moment, it's not the past: "Frank loves my mother's raviolis. Because she's abruzzese. They're the best cooks."